Discover postsExplore captivating content and diverse perspectives on our Discover page. Uncover fresh ideas and engage in meaningful conversations

My brother, Dr. Ubani Monday Onyekachi’s commentary on the Electoral Amendment Bill 2026 (Electoral Amendment Bill 2026: Clarifying the Architecture of Electronic Transmission and Collation published on his Facebook page on 18 February 2026) is framed as institutional moderation. In substance, however, it functions as a carefully constructed apology for legal ambiguity in a system that has already demonstrated its capacity for abuse. What he presents as “pragmatism” is, in reality, a defence of structural weakness. What he calls “evolutionary reform” is, in practice, managed stagnation.

At a moment when Nigeria requires maximal electoral certainty, his intervention normalises discretion, vagueness, and institutional latitude; precisely the conditions under which electoral malpractice thrives.

The core of Ubani’s argument rests on the claim that allowing Form EC8A to override electronic transmission in cases of “communication failure” is a reasonable safeguard.

This is misleading.

In modern electoral governance, redundancy is acceptable only when it is automatic, objective, and independently verifiable. The Nigerian amendment meets none of these criteria.

Under the proposed framework communication failure” is undefined, the declaration of failure is discretionary, the fallback document is manually generated and the same local officials implicated in manipulation control the process.

This is not redundancy, it is institutionalised loophole engineering.

In a country where elections are routinely contested over altered result sheets, missing forms, and substituted figures, any system that allows manual documents to supersede digital records is inherently vulnerable. No amount of rhetorical reassurance can change that.

A serious reform would have made electronic transmission the exclusive legal record, with physical forms serving only as archival backups, not alternative authorities.

Ubani gestures vaguely at “telecommunications improvements” while still defending a manual override. This contradiction is revealing.

If infrastructure has improved sufficiently to justify electronic transmission, then it has improved sufficiently to eliminate manual supremacy. If it has not, then electronic transmission itself is premature.

You cannot logically defend both positions.

What the amendment actually reflects is political compromise; lawmakers unwilling to surrender the traditional mechanisms through which elections are negotiated after voting has ended.

Ubani’s principal “solution” is to urge INEC to clarify the ambiguities through guidelines.

This is constitutionally perverse.

In a democracy governed by law, fundamental electoral safeguards must be embedded in statute, not outsourced to regulators.

By deferring core definitions to the Independent National Electoral Commission, the legislature weakens judicial enforcement, expands bureaucratic discretion, and politicises administrative rule-making.

Guidelines can be revised quietly, statutes cannot.

If the National Assembly were serious about transparency, it would legislate exact timelines, objective failure thresholds, automatic audit trails, and independent verification triggers.

Its refusal to do so is not accidental, it is strategic.

Ubani repeatedly appeals to “operational vigilance” and party preparedness. This shifts responsibility from institutions to victims.

Well-designed systems do not rely on constant alertness, they reduce the scope for abuse.

In mature democracies, electoral integrity is achieved through automated validation, tamper-resistant architecture, and minimal human discretion.

Nigeria’s amendment moves in the opposite direction. It expands discretion while preaching vigilance.

That is governance by moral exhortation, not by engineering.

Ubani’s most important observation is almost treated as an aside; the dilution of Section 137 reforms on documentary evidence. This is not incidental, it is central.

The 2022 reform sought to align Nigerian electoral litigation with modern evidentiary standards. It recognised that digital records, certified documents, and system logs should be sufficient proof of irregularities.

Reverting to mass witness production favours wealthy litigants, punishes smaller parties, exhausts judicial timelines and privileges logistics over truth.

It is a regression designed to make electoral justice procedurally inaccessible. In effect, it shields fraud through exhaustion.

By downplaying this rollback, Ubani understates its systemic danger.

The most revealing part of Ubani’s article is his conclusion; Electoral reform is evolutionary and not revolutionary.”

This is a rhetorical shield for inertia.

Nigeria has been “evolving” electorally for over two decades. The same disputes recur, patterns persist and courts are overwhelmed.

Incrementalism is defensible only when it produces measurable progress. In this case, it produces managed ambiguity.

What is evolving is not integrity, it is the sophistication of manipulation.

Ubani frames assent as a technical issue, it is not.

If President Bola Ahmed Tinubu signs a bill that preserves manual override and weakens judicial review, he will be endorsing structural opacity.

Civil society’s opposition is not sentimental, it is institutional.

A president committed to democratic consolidation would insist on digital primacy, legal certainty and judicial accessibility.

Anything less is complicity.

Ubani praises “institutional movement.” But movement toward what? The amendment preserves discretionary control, retains manual dominance, weakens litigation reform, defers clarity, and expands contestability.

This is not reform. It is institutional self-preservation by the political class through controlled uncertainty.

The National Assembly of Nigeria has not resolved Nigeria’s electoral crisis, it has managed it.

The closing appeal to faith and hope is emotionally appealing. It is also politically dangerous.

Democracy does not survive on goodwill. It survives on predictable rules, enforceable rights, technological safeguards, and judicial accessibility.

Where these are weak, appeals to patriotism become instruments of pacification. Citizens are not obliged to “have faith” in flawed systems, they are entitled to demand better ones.

In conclusion, Dr. Ubani performs a familiar function in Nigerian public discourse; he reframes structural defects as reasonable compromises and treats citizen skepticism as excessive.

By doing so, it shifts attention away from why discretion remains entrenched, manual override persists, judicial reform is reversed, and clarity is avoided.

His analysis is technically literate but politically accommodating. It explains the system without challenging its incentives.

And that is precisely the problem.

A credible electoral reform in 2026 should have made electronic transmission legally supreme, eliminated discretionary “failure” declarations, strengthened documentary evidence rules, reduced human intervention and embedded transparency in statute.

This bill does none of these decisively.

Until it does, Nigerians are not witnessing evolution, they are witnessing the refinement of uncertainty.

And uncertainty, in Nigeria’s electoral history, has always served one constituency; those who benefit from disputed outcomes.

Processed Superfruits Market in the United States (2026‑2034): Future Trends and Growth Drivers | #processed Superfruits

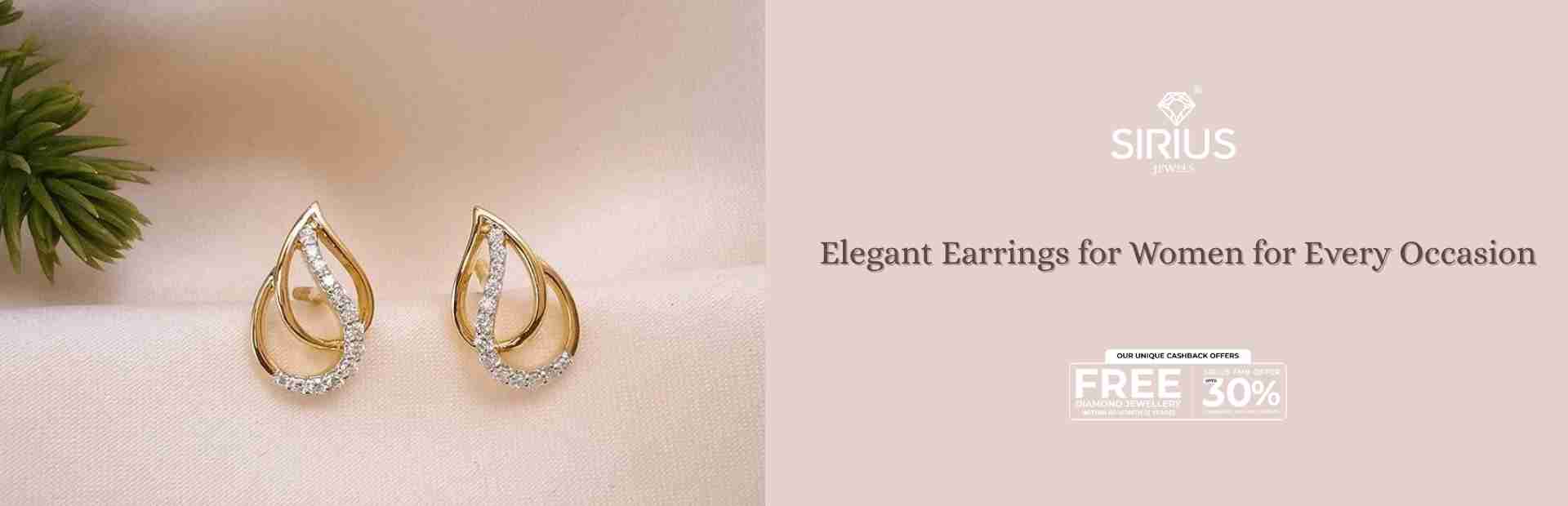

Latest engagement ring

EXPLORE NOW : https://www.siriusjewels.com/j....ewellery/rings/engag

Rat Model Market Growth Analysis: Key Players, Segments, and Future Opportunities | #rat Model Market

Algal Protein Expression Systems Market: Growth, Segments & Key Players | #algal Protein Expression Systems Market

Rejoinder: Why “Structure and Capital” Alone Cannot Explain Peter Obi’s Political Rise—or Limit His Future.

We dismantle the argument of Adeyinka A. Adebayo (in his Now let’s visit Peter Obi... Are you ready? Let's go..), point by point, without romanticism, without denial of reality, and without surrendering to fatalism.

The argument he has presented is seductive in its apparent realism. It clothes political conservatism in the language of “logistics,” “war,” and “capital,” implying that Nigerian democracy is an immutable marketplace where only the best-funded machines can prevail. But beneath this veneer of pragmatism lies a dangerous misreading of both history and the present moment.

To put it succinctly, Peter Obi is not politically relevant despite lacking traditional machinery, he is relevant because he disrupted it.

To reduce his movement to “vibes” is to misunderstand what happened in 2023, and why it still matters.

1. The False Gospel of “Money Determines Everything”

Yes, elections require resources. No serious actor denies this, but to argue that capital is the primary determinant is historically false. If money were decisive, Atiku Abubakar would already be president, several governors with vast war chests would never have lost elections and political upsets would not exist.

Yet they do, frequently.

Money amplifies political energy, it does not create it.

In 2023, Obi ran the most cost-efficient national campaign in Nigerian history. He mobilised millions without state treasuries, godfathers, or oil money. That is not weakness, it is proof of political innovation.

What frightens the establishment is not that Obi lacks money, it is that he showed money is no longer sovereign.

2. “Supply Chains” Without Moral Authority Are Hollow

Calling elections “logistical wars” is fashionable cynicism. But logistics without legitimacy collapse.

You may hire 176,000 agents, armies of lawyers and fleets of vehicles, yet if voters believe you represent corruption, stagnation, or elite recycling, that structure becomes brittle.

If we take a look at global politics, Donald Trump did not rise because of party machinery, and Barack Obama did not begin with donors, nor did Emmanuel Macron did inherit structures.

They built movements first, infrastructure then followed.

Obi did the same.

A structure that grows organically is more resilient than one rented for elections.

3. Tinubu’s “Depth” Is Also His Burden

Yes, Bola Ahmed Tinubu commands networks. No one disputes this.

But networks age, machines decay and patronage exhausts itself.

What is called “structural depth” is often accumulated political debt. Today, that debt is being paid in inflation, currency collapse, youth unemployment, and social discontent.

Political machines survive only while resources flow. When legitimacy dries up, structure becomes liability.

History has repeatedly shown this.

4. The Misreading of “Hardship Politics”

The claim that “hardship does not dethrone incumbents” is empirically wrong.

Hardship dethrones incumbents when it is persistent, personalised, and perceived as unjust.

Nigeria is approaching that threshold.

When citizens cannot afford food, fuel, school fees, or rent, politics stops being abstract. It becomes existential. At that point, “logistics” meets rage, and rage is the most powerful mobiliser in politics.

5. Party Pathways Are Not the Primary Battlefield

The obsession with ADC vs Labour Party misunderstands Obi’s political identity.

Obi is not primarily a party politician, he is a political symbol. His support base is ideological, generational, and civic.

Parties will orbit him, not the other way round.

This reverses traditional Nigerian politics, and that reversal is precisely why elites are uncomfortable.

6. “Donors in Kano and Gombe” Already Exist, They’re Just Not Oligarchs

The argument assumes that “real money” only comes from regional kingmakers.

Dead wrong.

Obi’s base is funded by diaspora professionals, SMEs, Tech workers, traders, doctors, teachers, and civil servants.

Thousands of small donors outperform a few godfathers. It is how modern campaigns work; slow, messy and democratic. And it scales.

7. The Trump Comparison Backfires

Trump returned because he captured a permanent social grievance.

So did Obi.

Both represent revolt against political establishments. But unlike Trump, Obi’s movement is younger, more educated, less violent, and more policy-driven.

That makes it more durable.

8. “Politics Is Not Therapy”, But It Is Legitimacy Management

Yes, politics is not therapy. Neither is it pure warfare, it is the management of collective consent.

Once consent collapses, no amount of money saves you.

The Soviet Union, Apartheid and Arab dictators had structure.

They all fell when legitimacy vanished.

9. The Real Fear Behind This Argument

If we are honest, this argument is not analysis, it is anxiety.

It reflects elite fear that; politics is slipping out of their control, voters are becoming autonomous, and money is losing monopoly power.

So they chant: “Structure. Capital. Structure. Capital.”

It is a chant meant to discourage insurgent politics.

10. Obi’s Real Advantage: Time and Demography

Obi’s base is young, Tinubu’s base is aging, and Time favours Obi.

Every year, new first-time voters enter, old patronage voters exit, digital mobilisation expands, and civic consciousness grows.

This is not sentiment, it is demography.

Conclusion: The New Equation of Nigerian Politics

The old model: Money. Structure. Victory

The emerging model: Credibility. Movement. Resources. Victory

Obi already owns the first two, the third will follow.

Not because of vibes but because credibility compounds.

Final Word

Peter Obi does not need to become a replica of old Nigerian politicians to win. If he does, he will lose. His strength lies precisely in refusing that template.

Those telling Nigerians that only oligarch-funded machines can win are not being realistic. They are defending a dying order.

And history is not on their side.